CLOCKWORK ANGEL

"A modern day Gamora, and a den of a thousand iniquities— that is your London."

Having satisfactorily passed his judgment on London, Axel Schauss crossed his arms and looked very pleased with himself. Inspector Shaw looked toward the new arrival from her majesties Special Branch, to see his impression of the prisoner, but his expression was inscrutable.

Mr. Victor Wyck’s sudden appearance had been a shock, but it was the speed at which he arrived after Mr. Schauss’ arrest that was most shocking. He’d walked into the station house less than a half hour after Mr. Schauss had been brought in, and Inspector Shaw wagered there were still persons in this building who did not know about the arrest.

“Do you have the man’s file?” Wyck asked raising his eyebrows.

He could clearly see it tucked under the inspector’s arm so he nodded and passed it to him. Wyck took it and folded his jacket across the back of the chair before sitting himself at the table in front of Schauss. He thumbed through the pages, giving each one only a cursory glance. After only a minute or two, he closed it and looked up at Shaw.

“I will require privacy for the questioning,” he said eying the Inspector and then the guard posted at the door.

Inspector Shaw felt his temper flare. Special Branch or not, it had been his hard work, and that of his men that had caught the killer. He would be damned if he would hand it all over now.

“My men and I worked hard tracking this man down Mr. Wyck, and I have quite a few questions of my own—”

“Of course Inspector,” he said, preempting the rest of his heated response. “I did not mean to imply you would not be present, I would just prefer the number of listening ears to be as small as possible.”

He gestured toward the guard and Shaw waved him off. The guard, a new recruit, Thompson was his name he thought, nodded and opened the door.

“Just give a good clap on the door sir, and I’ll be right outside,” he said before closing the door behind him and locking it with an audible click.

Shaw realized as Thompson left there was but two chairs, both now occupied, so he had to content myself with standing. Mr. Wyck slid the file back to him across the table and then looked up expectantly. Shaw realized, much to his surprise, he was waiting for him to begin the interrogation.

The Inspector laid his palms on the table and leaned over it as he looked at the prisoner. Schauss was smiling; he had been smiling since they’d apprehended him at the clock tower a few hours ago. It wasn’t the calm smile of a man expecting to get away with something. No. He had in fact, admitted responsibility for the killings when they’d seized him. His calmness was unnerving, but he’d seen it before—in men who held no remorse for the terrible things they’d done.

“We have questions for you Mr. Schauss,” Shaw said to him and he saw the man’s smile grow wider.

“Yes, yes inspector… but perhaps you could bring in a pot of tea? I know you English love your tea, and I have quite a long story to tell.”

Shaw glanced at Wyck, although he wasn’t sure why he did, this was his station house. Having Special Branch here unsettled him.

“Yes,” Wyck nodded as he caught the inspector’s eye. “I think tea would do just fine.”

Shaw rapped on the door twice and then spoke loudly through the door, “Thompson—bring us a pot of tea and three cups.”

“It’s Fitzgerald sir, and right away sir,” came a muted voice from the other side.

A long silence filled the time it took for… Fitzroy? Whatever his name was, to return with the tea. Thankfully, he also brought with him another chair and Shaw made a mental note to remember the lad’s name the next time. Shaw poured the tea for the three men and then settled into his chair next to Mr. Wyck.

The three men sipped their tea in silence for a time, and it was Mr. Schauss who finally spoke.

“It surprised me you took so long, how did you deduce my involvement in these matters?” He asked as he set his teacup on the table.

“It was your first victim… your wife. It took time to determine her identity due to the poor condition of her body, but when we did—we went looking for you.”

At the mention of his wife’s body, the Inspector thought he saw a waver in the man’s ubiquitous smile.

“Ah,” he nodded, and the room fell silent again.

“Why did you kill her? And her employer too? Why all of these ghastly murders Mr. Schauss?” Shaw was leaning over the table again, but before the prisoner could answer, Mr. Wyck interrupted.

“We should start at the beginning,” he intoned in a manner that seemed already bored with the affair. “I believe we met once before Mr. Schauss, you are the night watchmen at the Elizabeth Tower are you not?”

“Yes, yes… I remember you coming to see me,” he nodded. “I thought you had come for me that night, but you had been hunting someone else.”

Shaw looked and Wyck surprised, but he did not pause in his questioning.

“I understand that before you took your position as the night watchman at the clock tower, you were a clockmaker? And you immigrated to London from Vienna?”

Schauss smiled at him, “Yes, I come from a prestigious family of clockmakers… the finest in all of Austria. And yes, I agree we should start at the beginning—for only then can you understand the enormity of the miracle I have been witness to.”

“Miracle?” Shaw frowned.

“Please continue Mr. Schauss,” Wyck nodded as he ignored the inspector.

Special Branch had dispensed with the illusion that this was an investigation for Scotland Yard, and with a sigh, Inspector Shaw only nodded as he settled into his chair.

Mr. Schauss’ smile faded, and he seemed to take on a demeanor of great solemnity, spreading his arms as though he were delivering some kind of sermon.

“I was born in Vienna, and my family were appointed as royal clockmaker’s in 1761 by Empress Maria Theresa herself,” he began as he closed his eyes and Shaw could see how eager he was to tell his story. “You see… that is how my great grandfather saw it, the thing that would become his life’s work, and then his sons, and eventually my own—in a manner of speaking.”

“What did he see?” Shaw asked.

“The Turk.” Schauss replied as his smile returned. “Wolfgang von Kempelen’s automaton chess-playing machine.”

“What is the Turk?” Shaw asked, but Wyck raised a hand to quiet him.

“The Turk, dear inspector, was a miracle of machinery and ingenuity—or so it was believed. An automaton that could beat anyone at a game of chess, for even Napoleon Bonaparte lost to its strategic acumen.”

“Yes, but the Turk was revealed as a hoax,” Wyck added.

“True… true,” Schauss nodded as he affected the look of someone profoundly saddened by this knowledge. “But not for a long time. My great grandfather had been inspired by the machine, and after all—our family were renowned as the greatest clockmakers in the empire, and yet here was a machine far beyond the scope of our craft.”

“My great grandfather became obsessed with recreating such a machine. He threw himself into learning all he could about the crafting of automatons. After many years of hard work and diligence, he had become an expert in the manufacture of machines that could move in all manner of humanlike motion, down to even the delicate articulation of the hands. But that was the simplest part of the process; the real task was in creating a machine that could react to stimuli and process information. The hardest part gentlemen, was to make a machine that could think for itself. Sadly, by this time my great grandfather has become a very old man, and his work would eventually pass to his own son who took it up with as much zeal and fervor as had his father.”

Inspector Shaw could see that Mr. Wyck was riveted to the tale the prisoner was spinning, although he himself could not see what this had to do with the investigation. When Wyck had said to start at the beginning, he had no idea it would begin with the man’s ancestry. He was on the verge of bringing up this point when Mr. Wyck seemed to sense his imminent interruption and cast a quick and silencing glare. Shaw sighed and settled back into his chair, realizing he had little choice but to let Mr. Schauss ramble on.

“My grandfather realized that for the machine to think, he must imprint it with information with which it can draw its own conclusions from. So how could it be possible to store information in a machine?” Schauss paused for a moment to let the riddle dangle before us, but quickly returned to his narrative.

“His sister, my great aunt Gertrude, had been born blind, but they had taught her at an early age to use the French Braille system… using patterns of six dots to represent letters and numbers. My grandfather used a similar system to denote positions of chess pieces on a chessboard, which he stamped upon tiny brass cylinders that could be read by a delicate needle inside the machine. With this “brain” as it were, he was able to teach it numerous patterns and endgame scenarios so that at last, with two generations of work the Schauss family had created its own automaton chess-player.”

Shaw could see he was a little put off when neither he nor Mr. Wyck reacted with what he thought was the due amount of astonishment, but he shook his head with a wry smile and said, “There was just one major problem…”

“What was that?” Shaw asked and was surprised to find himself also drawn in to the old man’s story.

“It played terribly. While it was marvelous to watch, with its smooth articulate hands moving the pieces, and it is worth noting that unlike the Turk, it actually knew how to play the game. It almost always lost to even the most inexperienced of players. I could beat it when I was seven, having only learned to play that same year. No matter how many patterns he could embed within it, it was too easily fooled, too predictable, as it struggled to correlate the knowledge stored inside. Unlike the Turk, our automaton had no hidden compartment for a flesh and blood chess master to control and oversee its game. No, ours was the real thing, and actual thinking machine that played a truly awful game of chess.”

“Braille you say?” Wyck asked, rhetorically I think. “Fascinating.”

“It was a marvel to be sure,” Schauss smiled at him. “Even if it had not turned out the way they had hoped. My father hated the thing—because my grandfather had spent most of the family’s fortune pursuing it. It fell upon him to rebuild the depleted wealth of the family by dedicating himself to our original craft, clock-making. He made beautiful timepieces that still adorn the mantles of Vienna’s noble houses to this day, but he worked himself into an early grave too—the ticking of his own heart not as precise or infallible as the clocks he made.”

“It did not fall on me to step into his shoes because the era of handmade clocks was drawing to a close. Great factories like that in Lenzkirch were now churning out clocks by the hundreds, and modern gentlemen were less apt to repair their old timepieces when they could purchase one brand new. I kept up the business for as long as I could, the orders coming less and less, while still able to subsist in the meantime by the wealth my father had saved. But more often than not, I had time on my hands and nothing to show for it. So I took up the great work.”

“The automaton chess player?” Wyck asked.

“No,” Schauss said as he closed his eyes again, drawing on some old memory. “While I admired the chess player, it did not interest me to spend my life trying to teach it to play a better endgame. No, my passion had always been music. My mother had taught me to play the piano and my first works in my father’s workshop had been music boxes. No, the inspiration for my great work came at the Hofburg Theater when I watched a moving performance of Handel’s Messiah. Among other things, my family was devoted to the Roman Catholic Church. But I knew as I left the theater that night, I would create something far greater than an automaton chess player.”

“And what did you create Mr. Schauss?” Wyck’s eyes narrowed as he asked the question.

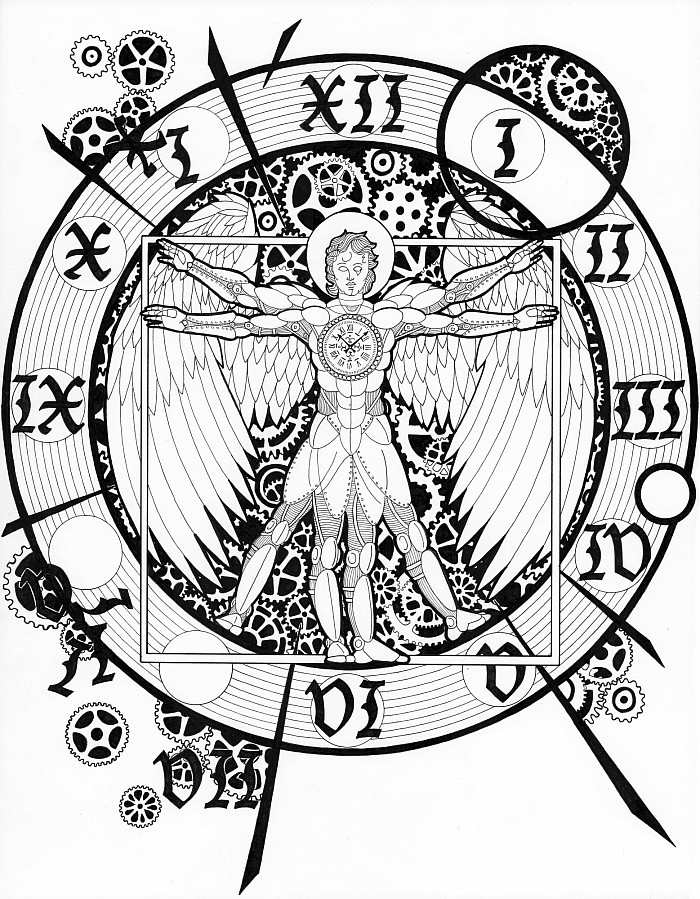

“I created an angel to sing the praises of our God almighty.”

“An automaton angel?” Wyck’s brow furrowed.

“Yes,” Schauss replied as he looked back and forth between us. “It was an automaton of copper, steel and brass—made by these hands, but it was truly an angel.”

Schauss paused as he let his revelation settle upon his two listeners. Wyck let the silence draw out and at last withdrew a pipe from his jacket on the chair and lit it with a match. He regarded Mr. Schauss with eyes that seemed to rarely blink even as the smoke curled from his mouth and nostrils. At last he took the pipe from his mouth and said just one word.

“Explain.”

Mr. Schauss smiled.

“My angel stands at one hundred twenty centimeters, about the size and proportions of a child, any larger and it would have been impossible to move, and it still weighs well over a hundred kilos. I constructed it of copper and brass; with each feather of its wings made from steel so thin and fine you could shave by it. It has a voice that is nearly human, and can sing so as to bring tears to your eyes. There is even a clock set into his breast, not as part of any essential function mind you, but there to honor our proud tradition Viennese clockmakers. It contains many mechanisms crafted by my grandfather and great grandfather, and yes—it can also play chess.”

“It sounds like such a wonder would have made you a wealthy man Mr. Schauss, but you’re the night watchman at the clock tower?” Shaw said, as he seemed to find much less relevancy in the old man’s story than did Wyck.

“Well yes,” he said as he raised his hands and shrugged. “That is if it had worked. Truth is my grand design was just well… too grand. There were too many layers of mechanisms to get them working together cohesively. It never walked well; the design of the automaton chess player was for it to always sit at the chessboard. You do not understand how complicated something like our sense of balance is to reproduce; and of course, every time it fell something broke, and I had to recalibrate everything. I had to fabricate many of its delicate components myself, and often the materials I was forced to work with were not up to the task. I had spent half my life working on it before I came to London, and less than half the mechanisms worked at any given time.”

“Yes, Mr. Schauss,” I cut in despite the glare from Wyck. “Our records show you came to the city ten years ago—”

“Eleven,” Wyck corrected. “The file says eleven years ago”

“Eleven years ago,” I turned back to Schauss. “Let’s pick up there shall we?”

“I left Austria when I was forced to close our family’s shop. I scraped together what remained of my family’s wealth and decided I would follow in the footsteps of my inspiration George Friedric Handel, and find my destiny in England. I’d hoped at least, that in the greatest city in the world there might be work for a man who could repair clocks and pocket watches, and I’d also hoped its factories and advancing technology would afford me superior materials for my great work.”

“The file says the ship‘s captain married you and your wife,” Shaw said as he opened the file, rifling through its contents. He could see the flicker of uncertainty across the man’s face at the mention of his wife, that moment when the smile was more forced than genuine.

“Yes. I met my Gretchen on the ship to London. She’d been so young and beautiful, only nineteen and still very naïve. But she’d been fearless. She had sold everything she owned to book passage on that ship. She didn’t have a penny left to her name, nor did she speak even a single word of English, but there she was—bound for London. I was almost forty. It was when she heard me speaking English, I’d always had a knack for languages that she insisted I teach her during our long voyage. I admit I was quite taken with her from the beginning. It is only now when I look back, I realize much of her attraction was perhaps more to due with money than my charm. We grew close very quickly, and the evening before we were to arrive in London, we begged the ship’s captain to marry us.”

“We arrived in London as Mr. and Mrs. Schauss, and I used the last of my family’s money to set up a shop for repairing watches, clocks, music boxes, and anything mechanical brought to me. Those first few years were good to us, and whatever her reason’s for marrying me, she proved a good wife and dutiful homemaker. For whatever reasons, God did not grace us with children, but we were content enough for a while—or at least for my part, I was happy.”

“And yet she and her employer were your first victims.” Shaw said as he drew a piece of paper from the file. “She was working as a cook at the home of a Mr. Bartley, a solicitor. The housekeeper discovered their bodies, naked and mutilated, in the bed of the master bedroom on the morning of September sixteenth. Evidence seems to indicate the two were having an adulterous affair, collaborated by testimony given by the housekeeper. So what happened Mr. Schauss?”

Shaw saw him blink several times, and it looked as though his eyes had been on the verge of showing tears when he cleared his throat and continued his story.

“Times grew hard. The recession in the economy dampened our business considerably, but it grew worse when the local trade union took exception to me. I was a Catholic, and they would not accept my membership amongst them. My wife begged me to join the Anglican Church as she had done, but I refused, for God has but one true church on earth, and it lies in Rome. They spread rumors, drove away my customers, and made it impossible to keep the business open. Eventually, she went to seek work herself to make ends meet. Luckily, she was an excellent cook and a gifted pastry chef. She took some of her strudel to the first advertisement she answered and was hired. I had thought this a stroke of luck and a testament to her talents in the kitchen. It hadn’t occurred to me the gentleman might have been drawn to her other qualities. As for myself, I took work keeping the gaslights lit in the great clock tower at night; this allowed me to do odd repair work during the day as I found it. But with Gretchen gone all day, and myself all night, a distance grew between us.”

“So you killed them over the affair… but why the others?” Shaw plied him impatiently.

“I didn’t kill them.” Schauss said. “They were punished for their sins.”

“By who?” Wyck asked, but something in his tone sounded as if he knew the answer already.

“By God’s own wrath,” Schauss snarled, the smile at last falling from his face. “God saw their unholy lust and sent my angel to smite them.”

“The automaton?” Shaw’s face looked incredulous. “Surely you’re joking.”

Mr. Schauss laughed then, a manic tittering sound that grated on the nerves. “I can’t explain it either, except to say it was God’s work, a miracle. About a year ago something changed with my great work. Things that never worked before began working, and far better than I could have imagined. It could at last walk gracefully, and sing the Messiah Chorus, hell it could even beat me at a game of chess. But what happened next showed me it was not my hands at work here, but the Lord almighty.”

“What happened?” Wyck asked as he set his pipe aside and folded his hands on the table. “Tell me.”

“It flew,” he said as his eyes widened. “It actually used its wings to fly—more than a hundred kilos of metal, on wings designed to be purely ornamental.”

The man was off his nut, Shaw thought to himself. He looked at Wyck whose expression remained inscrutable, and he turned back to Schauss as he leaned over the table.

“You mean to have us believe your automaton committed all of these murders?”

“It was not murder, but God’s own judgment.” Schauss replied as he stiffened, refusing to be cowed by the looming inspector. “My angel sees the sins of man, and where he sees it—he acts as God wills.”

“This is madness,” Shaw exclaimed, shaking his head as he turned to Wyck. “The man is completely around the bend and wasting our time—”

“You said the angel killed your wife and her lover for the sin of lust,” Wyck interrupted as he glared at Shaw once more. “Why then the others?”

“London is drowning in sin,” Schauss muttered ruefully as he matched Wyck’s gaze. “My angel spoke to me of a white light surrounding everyone he looked at, but sometimes that light was stained with color—as my wife’s was, stained in deepest blue, the color of lust.”

“And Mr. Parker? Who owned all of those tenement houses in Whitechapel?” Wyck probed further, and Shaw was surprised how much he could recall from his cursory glance of the file earlier.

“Greed is yellow, and that man had made a fortune renting those rat infested holes to the desperate, and throwing them on the streets the minute they were a penny short on their rent.” Schauss replied.

“What about the Hooligan Gang in St. Giles? What was their sin?”

“Reddest wrath. My angel had seen them revenge themselves on a rival gang earlier that evening, killing two of them.” Schauss said as he folded his arms over his chest, seeming to relish this line of questioning.

“Yes, but the fire there killed a lot more than the Hooligan Gang, more than a half-dozen women died in that fire too,” Shaw interjected at the smug-looking Schauss.

“They were whores.”

Shaw felt his temper rising and fought to keep it under control. He turned away and rubbed his face with his hands as he composed himself. “Jacob Savoy was a thief, if I were to guess—envy, perhaps?”

“Green,” Schauss’ grin widened and Shaw was nearly overcome with the urge to strike the man.

“Mr. Dubois, found outside his gentlemen’s club on the morning of the eighteenth, was he pride?” Wyck seemed to enjoy this game as much as Schauss, but Shaw disliked it immensely.

“No, my angel saw him stained in lightest blue,” Schauss replied with a playful, if sickening, wink.

“Ah,” Wyck nodded. “Sloth then.”

“So that leaves us with just Gluttony and Pride,” Shaw said. “I guess it is a good thing we caught you this morning when we did.”

There was a rattle of keys at the door, and Thompson slipped into the room. He looked straight at Schauss for a moment and then leaned to whisper in the inspector’s ear.

Wyck smiled as he nodded to himself, the first real expression Shaw had seen on his face. “My guess is that there has been another murder matching the same method prescribed in that file you hold.”

Shaw looked down at the file in his hand and frowned, letting it drop onto the table. His face did not soften when he turned to look at Wyck.

“They found a body this evening mutilated outside the Lucky Thunder,” Shaw replied, and he couldn’t decide which of the two looked the more smug. “It is a well-known opium den.”

“Gluttony” the two of them said in unison as they turned to look at each other, one smiling and the other expressionless.

Shaw rubbed his eyes and sighed. He turned toward the guard, what’s-his-name.

“Take the prisoner back to his cell,” Shaw said and then turned toward Wyck. “I am going to the Lucky Thunder, would you like to ride along?”

Wyck smiled as he stood, taking up his jacket from the chair and his pipe from the table. “No, thank you Inspector. I have my own report to attend to, but perhaps you’d be so kind as to send for me when the next murder reveals itself? We still have Pride to account for…”

He didn’t wait for an answer but swept passed them and out the door. Shaw glowered at his back but said nothing. When he looked at Schauss, he was smiling. He turned to Fitzgerald.

“Take him back to his cell.”

* * *

“Father,” came the beautiful voice in the dark.

Schauss looked up from the bench on which he sat and saw a shadow pass over the barred window above him. He smiled and crossed himself as he finished his prayer.

“You have a father far greater than me,” Schauss said as he came to stand below the window. He looked up and could see the beautiful face of his great work looking down at him, and it filled him with joy.

“But it was still your hands that crafted me,” the angel replied. “And I would ask something of you, if you would grant it?”

“Anything,” Schauss replied as he reached up through the bars and felt the cold hand of his creation take his own.

“I have no name father,” came the sweet voice.

Schauss closed his eyes for a moment, and then opened them, “I would call you Aspirial, for you are my avenging angel.”

“Aspirial,” said the voice, and it sounded far more lovely as he said it.

“I am so very proud of you my son,” Schauss whispered as tears welled up in his eyes. “So very proud…”

“I know father.” Aspirial said as his eyes flashed violet. His grip tightened on Schauss’ own as his wings shot through the gaps in the bars and he saw his life’s blood sprayed across the stonewall of the cell. He hadn’t even felt it as he fell backward, his warm blood pooling around him. Schauss looked up and saw that his creation was gone, but a movement at the cell door drew his gaze. He saw a veiled lady dressed in the black of a widow’s mourning dress. Was it his Gretchen come to see him in his final moments? No, he realized as his vision began to dim—it was the angel of death.